Elephants always have priority

Botswana | Chobe | Anno 2022

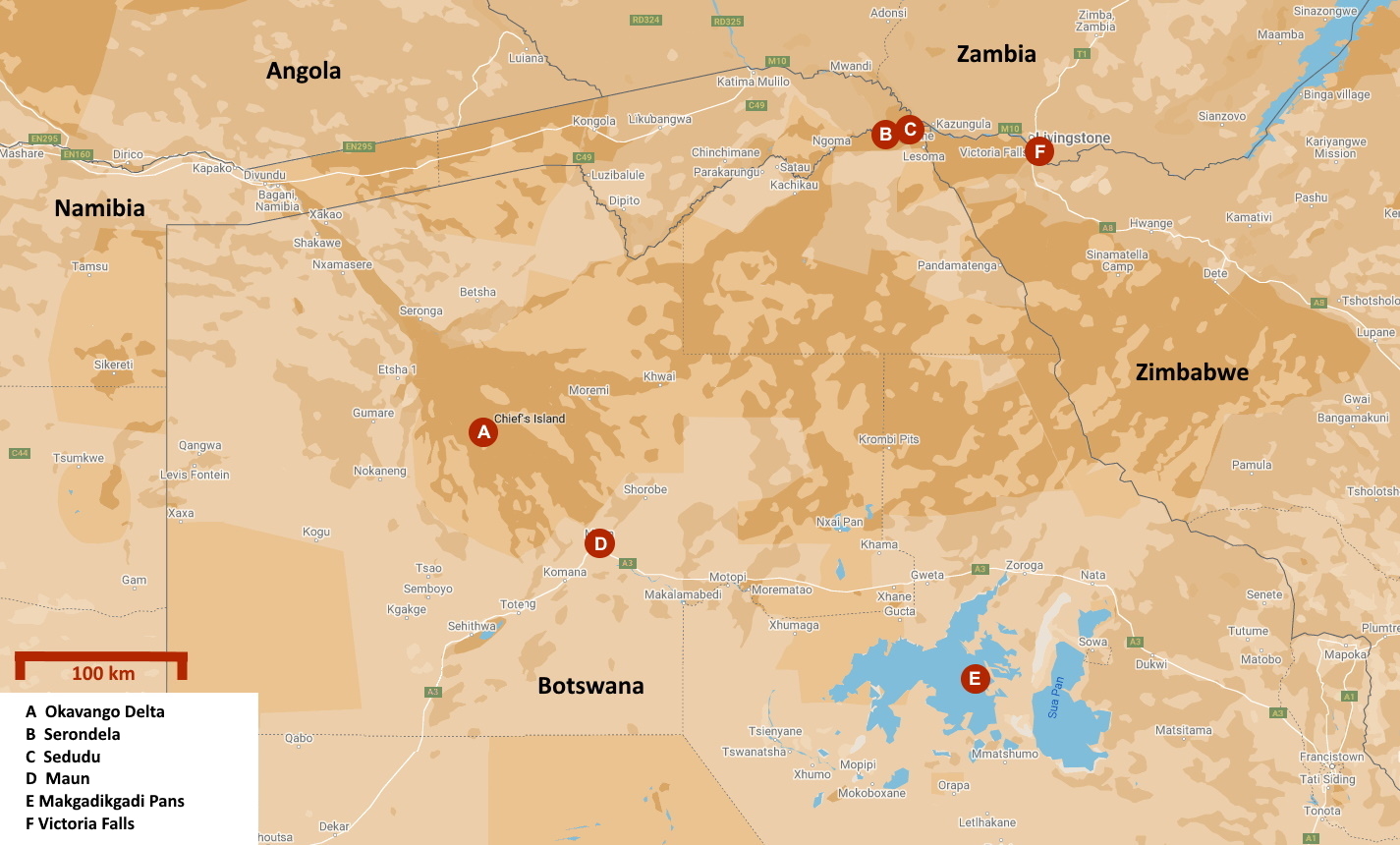

It is a peculiar river, the Chobe. Like the Okavango, it rises in the northern highlands of Angola – they call it the Kwando there – and flows straight through the Namibian Caprivi Strip into Botswana. Its fate seems sealed there. Like the Okavango, the Kwando will come to a dead end in the desert, creating a magnificent inland delta.

Yet that is not the case. Because in Botswana the Kwando immediately hits a fault line in the earth's crust. It forces the river into a highly unusual manoeuvre – it follows a ninety-degree angle. Named Linyanti, the river continues its course in a north-easterly direction, creating the marshes of the same name.

Beyond the swamps, the Kwando takes the name of Itenge. A little further on, the Tswana call it Chobe. Thus it flows into the mighty Zambezi.

But that doesn't always go smoothly. Like the Okavango, the slow-flowing Chobe has to deal with intense evaporation. Sometimes the water level of the Chobe is so low that the water of the Zambezi seeps into its bed. Some therefore say – incorrectly, incidentally – that the Chobe flows in two directions.

The National Park that gave the river its name boasts one of the largest concentrations of game on the African continent. Today it covers 11,700 km² – more than a third of Belgium. Savuti and the Linyanti Swamps are part of it, but by far the most popular spot is what is called the Chobe River Front, a forty-kilometre stretch along the river.

Serondela is one of the places from which you look out over the floodplains of the Chobe. The river's lush flood plains are teeming with waterfowl and, especially in the dry season, provide a vital watering place for a host of mammals – antelopes, zebras, buffaloes, giraffes, elephants. On the riverbank, on the other hand, the dry, sandy slopes are quite steep. Grazers have to be wary between the trees, because lions are constantly lurking.

Sedudu is some distance downstream. What makes this island so special is the fact that it barely rises above the water surface. In fact, it is as flat as a pancake. It is completely soaked with water, partly soggy even. The grass is green all year round. A paradise for the animals, at least as far as they can and want to swim. Lions do not like such a swim. That is an additional advantage, because it makes the island safer for the other animals.

For a long time, both Botswana and Namibia laid claim to the island. It was not until 1999 that the International Court of Justice in The Hague ruled that the island belongs to Botswana. The fact that the Chobe on the north side of the island is much deeper than on the south side was the deciding factor. Sedudu is now part of Chobe National Park. The island is off limits to humans, only animals are allowed. Fishing is no longer allowed in the southern arm, but it is still allowed in the northern arm. Namibian fishermen eagerly use this.

The real stars of the park are the elephants. Apparently they know that themselves. Because they invariably take pride of place at the waterholes. Other animals have to wait their turn, whether they like it or not.

These elephants are probably the largest contiguous population in the world. There are 50,000 in Chobe alone, but there are 120,000 scattered across Botswana. Not bad, considering Botswana only had a few thousand elephants at the beginning of the 20th century. Over a period of 100 years, this is an annual growth of 3 to 4%.

Botswana's escape from the massive illegal trapping that decimated other elephant populations in the 1970s and 1980s has played a major role in this. In terms of body size, Botswana's elephants are admittedly the largest of all living elephants. However, their tusks tend to be rather brittle and short, making them less sought after by poachers. This may be due to a lack of calcium in the soil.

During the dry season – from May to October – the elephants like to stay near the Chobe and the Linyanti. When the rainy season begins, they move to the south-eastern part of the park. That is a journey of two hundred kilometres. Nothing or no one can divert them from their path. One school experienced this when it surrounded its grounds with a sturdy metal fence. The pachyderms paid no heed to it and walked right through it, completely destroying it.

Jaak Palmans

© 2022 | Version 2022-12-16 15:00