Nobody knows whhen the water will come

Botswana | Savuti | Anno 2022

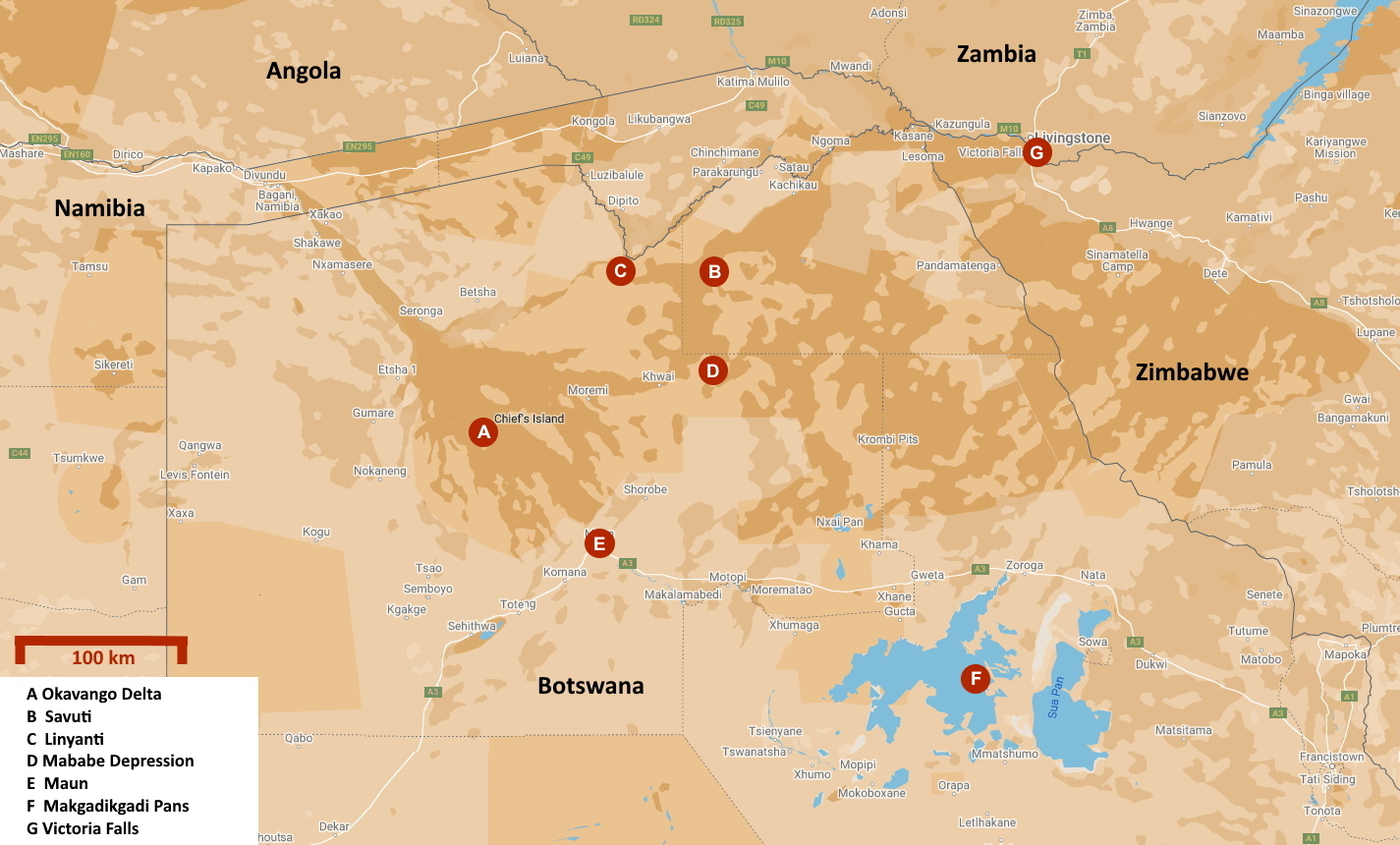

When David Livingstone visited Savuti in 1852, he saw a lot of water flowing through the water way we now call the Savuti Canal. That water came from the marshes of Linyanti on the current border with Namibia. These swamps were in turn fed by the Selinda, a tributary or rather a spillway of the Okavango.

In fact, most of the Selinda's water flows neatly out to sea through the Chobe and Zambezi. The fact that water "leaks" to this desert area via the Savuti Canal is therefore actually an anomaly. But that is due to the presence of the Mababe Depression, an immense basin of 50 by 90 km into which the water flows. This lower area is a remnant of a huge lake, Lake Makgadikgadi, which originated here two million years ago and only dried up ten thousand years ago. The bed of the Savuti Canal is therefore most likely a remnant of one of the rivers of that time.

In 1888 the water suddenly disappeared. The Savuti Canal was dry for nearly eighty years. Until 1957. Then the water suddenly flowed through the river bed as usual. Only in 1966 and 1967 did the water disappear briefly, but it came back again. In 1982 another dry period started, but this time of a long duration. It wasn't until 2008 that water came back, although you shouldn't exaggerate that. Because it took until 2010 for the water to reach the Mababe Depression, a mere hundred kilometres away.

The wealth of water was a boon to the region. But it also had a downside. At the park ranger's headquarters, the road through the park had become impassable. Soon a bridge was built over the Savuti Canal. Unfortunately, the water has disappeared again since 2013. The bridge now stands seemingly useless above a bone-dry riverbed.

The coming and going of the water puzzles everyone. It has nothing to do with high or low water levels of the Okavango or the Zambezi. Presumably it is tectonic movements that cause this bizarre phenomenon. After all, we are here at the southern end of the Great Rift Valley, where continents are being pulled apart. This can cause deformations in the earth's crust, causing layers to be lifted. This can make the water flow, or stop it. Just like you can make water flow through a gutter by lifting it a little on one side or the other.

Be that as it may, every time water flows through the Savuti Canal, the local ecosystem explodes. Zebras, wildebeest and even buffaloes flock here en masse, with predators following in their footsteps. Nevertheless, even though the area is still dry as a bone at the moment, there is a lot to experience.

Also typical of Savuti are the Gubatsa Hills. These are isolated rocky hills with names like Leopard Rock, Kudu Hills and Ghoha Hill. On average, they rise ninety meters above the flat landscape. Geologically, they are dolomite peaks. They remind us of volcanic activity that must have taken place here 980 million years ago.

But Savuti owes its real fame not to its hills, not even to the vagaries of its channel. It is lions that put Savuti on the world map. Because in the nineties of the last century it turned out that these lions were capable of killing an elephant. A feat never before seen anywhere else in Africa. Twenty-seven adult lions waited for elephants at the watering hole at night and isolated and killed one of them. That way they had enough to eat for a whole week. In total, at least eleven such daring exploits are known. But nowadays we should not expect such stunts to happen again. Due to the drought, the lions have broken up into groups that are too small to pose a serious threat to an elephant.

Jaak Palmans

© 2022