Meet the master builders

Botswana | Okavango Anno | 2022

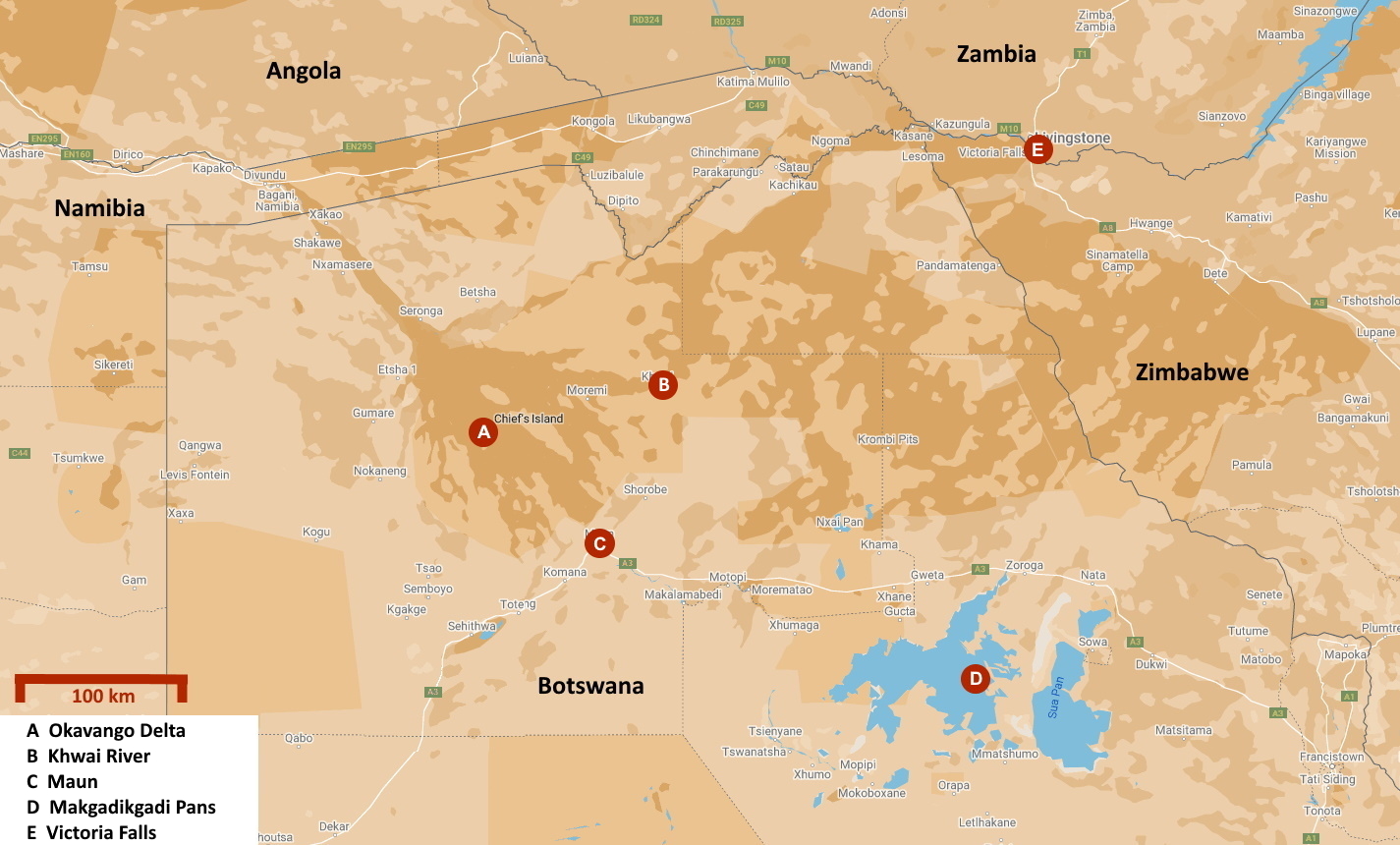

With an area of 18,000 km² – more than half of Belgium – the Okavango Delta is one of the largest wetlands in the world. Annual floods make it one of the richest and most diverse habitats in Africa. Many animal species feel at home in the maze of winding channels, lagoons, oxbow lakes, islands, floodplains and swamps.

That has been the case for many tens of thousands of years. Yet the image of an immutable delta is very misleading. Because the delta is constantly moving. Papyrus growth blocks channels, changing the flow pattern. Channels silt up with sediment so that channels become islands and islands become channels. Even tectonic shifts – after all, we are at the southern end of the Great Rift Valley – have an impact. However small such shifts are, given the drop of only two metres over the entire area, they can have major consequences for the flow and distribution of the water.

All this would normally lead to the characteristic maze of waterways disappearing almost unnoticed. But for now there is no cause for concern. Three animal species play a key role in maintaining the delta. Without the essential contribution of these master builders, the delta would no longer be the delta.

First, there are the hippos. They are the real master builders of the Okavango ecosystem. If hippos did not penetrate the reeds and sedges and graze the bottom of the channels, the vegetation – especially the aggressive papyrus – would gradually choke the waterways. The water would take a different route around the delta. While grazing, the hippos even are constantly opening new channels.

The crucial role played by hippos became abundantly clear in the southwestern part of the delta at the beginning of the twentieth century. Hippos were hunted on a large scale there. As more hippos died, the channels became less and less open, diverting the water and draining it southwest.

But elephants also unconsciously make their contribution. Like hippos, they imperturbably make their way through the water and keep channels open or even create new ones. In addition, elephants see trees as a source of food. With the greatest of ease they break down sturdy trees and nibble on the branches. In this way, densely forested areas are being transformed into more open grassland. The apocalyptic image of all those broken trees makes us shudder, but for antelopes, zebras and wildebeest the open grassland that is created is a blessing. Because it is now much more difficult for predators to approach them unnoticed.

Last but not least, there are the termites that play a fundamental role in the formation of the Okavango Delta. In the waterrich environment, termite mounds grow into round islands. No less than seventy percent of the islands in the delta were created in this way. Often the mound is colonized by a tree growing from seed deposited in animal faeces – usually a wild date palm, fan palm or jackalberry. Deposition of sediment on the walls of the termite mound further increases the surface area of the island.

Oddly enough, that eventually leads to the botanic death of the island. Like the tree, the plants absorb water and release it again through evaporation under the persistent heat. What remains is a white, salty substance around the termite mound. Vegetation can no longer survive in this toxic environment, apart from some saltgrasses.

As if they don't contribute enough to their habitat, termites are also an essential part of the food chain. In early summer, the air is filled with flying termites. Once they emerge from their mounds, they provide a feast for birds, reptiles, frogs, and other animals.

The Khwai River is one of the permanent rivers of the Okavango Delta where hippos like to hang out. It rises out of Xakanaxa Lagoon and winds eastward in a hundred turns through the floodplain of its own making.

Jaak Palmans

© 2022 | Version 2022-12-17 15:00