A gift from the Okavango

Botswana | Okavango | Anno 2022

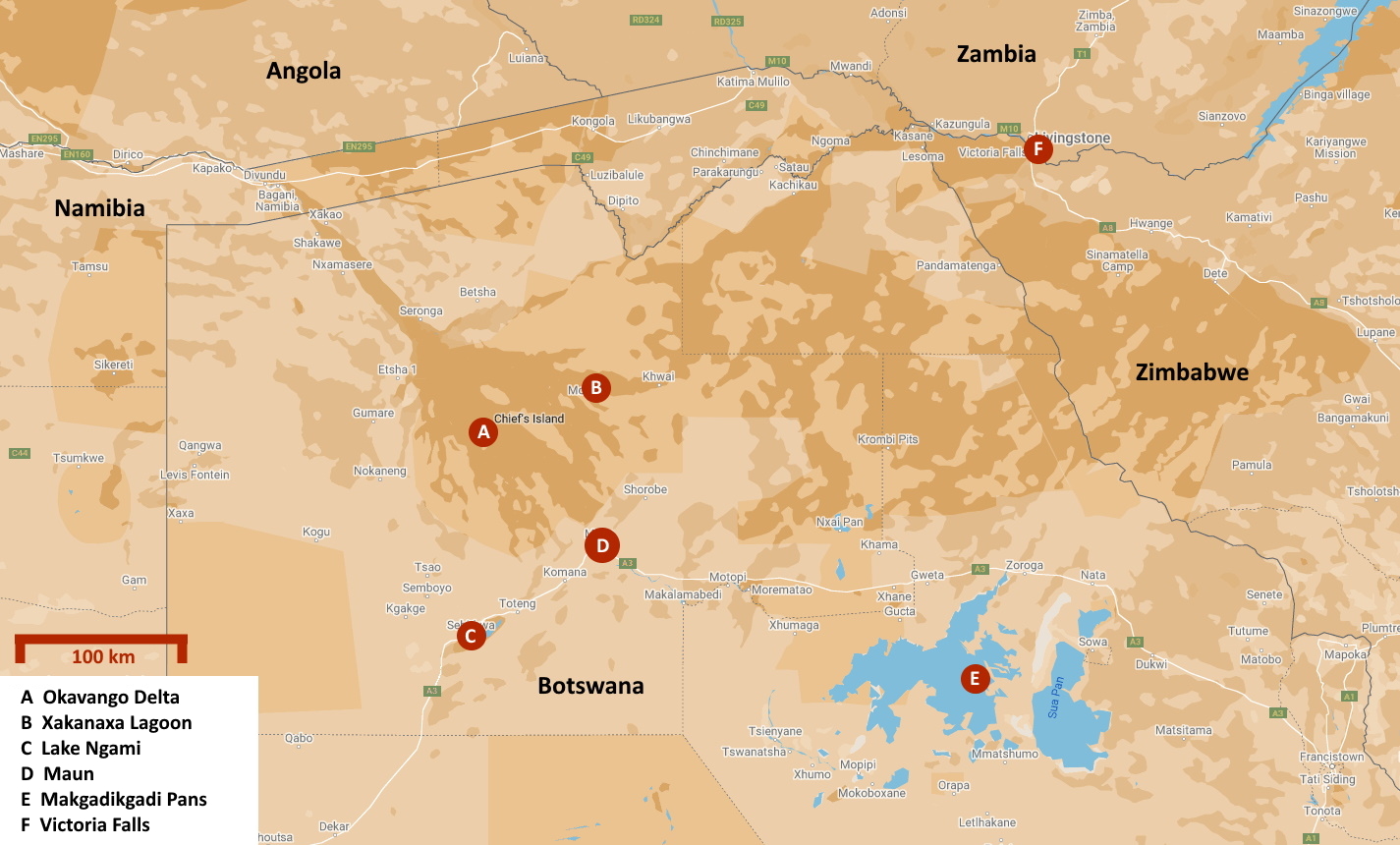

In the highlands of Angola, where the Okavango originates, tropical rainfall peaks in January each year. Barely a month later, after a journey of more than a thousand kilometres, that water flows into the Okavango Delta in Botswana. But there the flood almost comes to a standstill. It takes four months for the waters of the Okavango to cross this delta – a distance of only 250 km. The reason for this is not far to seek. The inner delta, with an area of 18,000 km² or more than half of Belgium, has a drop of barely two metres.

And the Okavango is partly to blame for that. Because the river carries fine sand. In the past, in drier times, it was the wind that spread this sand over the plain. Now the river is responsible for the thickening. Where the water flows slowly, those grains of sand whirl to the bottom. In some places the sediment layer has grown to a respectable thickness of 270 metres. This is how this flat plateau was created here, in the foothills of the Great Rift Valley, at an altitude of about 930 metres.

What makes this inland delta so special is the fact that the waters of the Okavango never reach the sea. The river just comes to a dead end in the Kalahari desert. A bit like a water hose that you empty into a sandbox, but much bigger. A maze of winding channels, lagoons, oxbow lakes, islands, floodplains and swamps is the result.

The annual floods make the Okavango Delta one of the richest and most diverse habitats in Africa. Just as Egypt is a gift from the Nile, this inner delta is a gift from the Okavango.

In short, the Okavango Delta is a place where animals feel at home. Water is plentiful. This is especially important during the winter months – from June to September – when not a drop of rain falls in the delta. So the flood from Angola comes at just the right time. Animals are drawn to it from miles around. This creates one of Africa's largest concentrations of wildlife.

Evaporation is the biggest enemy of this water. Thirty-five percent evaporates directly at the surface. Sixty percent is absorbed by plants. There it evaporates through the stomata of the leaves, a process that provides the plants with essential cooling. What remains of the water – about five percent – seeps into the subsoil or flows on to Lake Ngami.

In this fascinating biotope, some islands disappear completely under water only to reappear at the end of the rainy season. Some areas are permanently under water, while others completely escape the flooding.

The local vegetation therefore falls into two main types. On the one hand you have dense clumps of papyrus reeds and other aquatic plants in the rivers and channels of the floodplains. On the other hand, the slightly higher parts are occupied by areas of forest and savanna. Both biotopes attract specific animal species.

On the eastern edge of the fanshaped inner delta, in the beating heart of Okavango, lies Xakanaxa. It is one of the lagoons that are permanently flooded. It is teeming with animals. Large herds such as on the open savanna of the Kenyan Masai Mara or the Tanzanian Serengeti are not found here. Here it is the unprecedented diversity of animal life that will amaze you.

Jaak Palmans

© 2022| Version 2022-12-16 15:00